Newton's Second Law

- brianaull

- Nov 29, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2025

A challenge quiz about Newton's Second Law

Isaac Newton revolutionized physics. He discovered how to predict the orbit of a planet or the trajectory of a golf ball, using the same simple equations. But, Newton's physics contradicts many of our "commonsense" beliefs.

How does your intuition about the physical world compare to Newton's physics? Take this challenge quiz about his Second Law.

A short fall

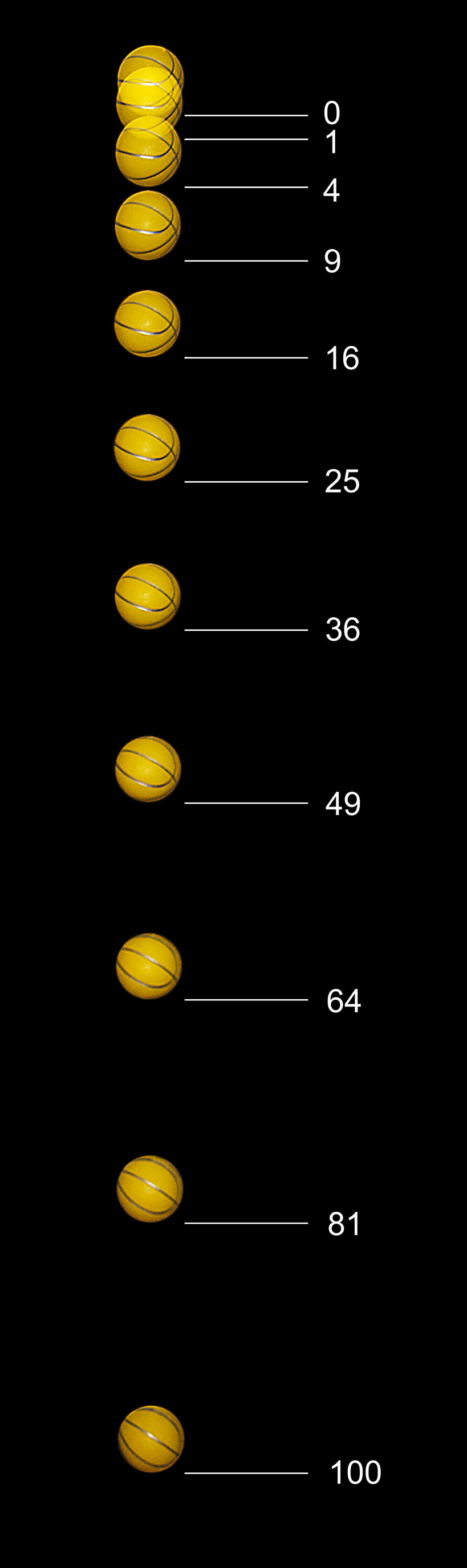

A ball is dropped and falls for half a second. We take a multiple-exposure photo using a strobe light flashing every 1/20th of a second. Which of these three drawings best shows what the photo will look like?

Here is an actual strobed picture of a tennis-ball-sized ball falling. The ball travels farther and farther during each successive time interval, so it's accelerating. The best match is answer B.

This introduces us to Newton's Second Law, which says that a force, in this case, the downward force of gravity, causes an acceleration.

One misconception is that an object falls at a constant speed. This may be another example of intuition conditioned by living with friction. If we let the object fall for long enough, air resistance increases to become strong enough to check the acceleration. Below is an illustration of this. A skydiver jumps from a plane. At first, he accelerates because of gravity. But his speed then levels off because the braking force of air resistance offsets gravity.

Newton's Second Law is expressed by the famous equation F=ma. If we put it in the form

a = F/m, it just says that the acceleration of an object equals the net force on it divided by the mass. The stronger the force, the more rapidly it changes the velocity. But also, the more massive the object, the more force is needed to get a certain amount of acceleration (or deceleration or change in direction). Mass is basically the amount of matter, and also tells us the amount of inertia. A bowling ball is harder to accelerate than a basketball, and once it's rolling, it's also harder to slow it down or change its direction.

Two short falls

A basketball and a much heavier medicine ball of the same size are dropped from six feet high. Which one hits the ground first?

a. The medicine ball b. The basketball c. They hit the ground at the same time

Here's a video of the experiment, along with students trying to explain why the two balls hit the ground at the same time. Many pick the right answer, because they've heard stories about Galileo doing a similar experiment on the Tower of Pisa. But then they often can't explain how Newton's physics gets us to the right answer.

"Weight" is just a synonym for the force of gravity on an object. The English pound is a unit of force. The force of gravity (the weight) increases in proportion to the amount of matter (the mass). So why do the objects fall together if the force on the heavier ball is greater? As the video explains, the heavier ball also has more inertia by virtue of having more mass, so a greater force is required to get a given amount of acceleration. These two factors exactly offset each other.

Again, we live in a friction-ridden world, so that there are many scenarios where air friction causes the heavier object to hit the ground first. But once we get rid of the friction, even a feather accelerates at the same rate as a heavy metal object.

Now let's look at a combination of horizontal and vertical motion.

It's a ball, it's a bullet, it's a rocket!

Two balls are at the same height. One is dropped. At the same time, the other one is launched sideways. Which one hits the floor first?

a. The dropped one, because it has a shorter distance to travel b. The dropped one, because the launched one will not start to fall until its horizontal motion slows down enough c. The launched one, because it is going faster d. They both hit the floor at the same time e. It depends on how fast the second ball is launched sideways f. It depends on which ball has more mass

Here's a video of a spring-loaded rod that drops a ball at one end while pushing another one sideways at the other end. The balls are small and heavy enough not to be disturbed much by air resistance. The correct answer is d.

The Roadrunner, a children's television cartoon, depicted the coyote running off the edge of a cliff. The coyote would go horizontally for a time, as if his horizontal speed somehow made him immune from the downward pull of gravity. Then, once his horizontal impetus wears off, gravity would take over and cause him to fall straight down. In one study of high school and college students, 40% actually picked answer b. Their intuitive notions aligned with "coyote physics" rather than Newton's physics. This misconception can be found in the writings of medieval and ancient thinkers, who thought that whenever there is motion, there must be some kind of force sustaining it, which then wears off.

Below shows how the dropped ball and the launched ball would show up in a multi-exposure photo with a strobe light flash every 1/10th of a second. Horizontally, the launched ball maintains constant speed because there's no horizontal force. Vertically, the two balls accelerate together, just like the basketball and the medicine ball we saw earlier.

Notice that at the very beginning of the launched ball's trajectory, the force of gravity is at right angles to its velocity. So initially, the effect of that force is to change only the direction of motion without changing the speed. The ball "wants" to keep going straight, but gravity deflects it downward.

Even a speeding bullet starts falling as soon as it exits the gun barrel. The bullet travels in an arc, not a straight line. Hunters "sight-in" their rifles to compensate for this. For example, a hunter might "sight-in" for targets at 100 yards. He'll adjust the telescopic sight on the rifle so that the bullet is launched in a direction slightly above the target.

Now suppose we could launch a ball sideways at some tremendous speed. In practice, we'd need to worry about the air friction, but suppose we could do this experiment in a giant vacuum chamber. If we pick the speed just right, close to 17,000 mph, something remarkable happens. Now the ball is going so fast that by the time it falls one foot, the surface of the Earth (which is not flat) has also curved one foot. Even though the ball is on a curved free-fall trajectory, it stays the same distance above the ground. The force of gravity, which points toward the Earth's center, stays perpendicular to the velocity, constantly deflecting the ball on a circular path. This trajectory, shown below, has a technical name. It's called an orbit.

Comments