Buoyancy: What makes things float?

- brianaull

- May 30, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2025

A genius runs home naked

Archimedes (287 – 212 BC) explained buoyancy, the force that makes things float in water. It all started when he proved that a metalsmith had tried to cheat the king. The king had hired the smith to make an elaborately shaped crown out of gold. The king thought that the crown was too light to be pure gold. He asked Archimedes to prove that the smith had mixed in a cheaper metal. But Archimedes could not cut, melt, or otherwise damage the crown, as it was a sacred object.

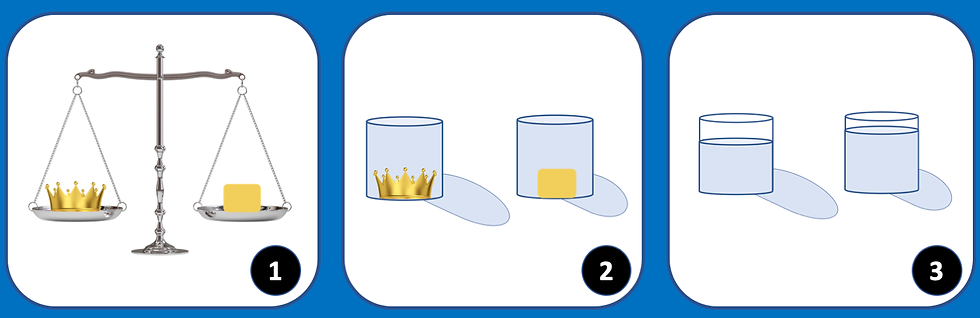

While pondering this problem, Archimedes stepped into the public bath, causing it to overflow. This triggered a flash of insight. He was so excited that he jumped out of the bath and ran home naked, shouting "eureka!" A bucket of water, he realized, could be used to measure the volume of any object, even one with an irregular shape. Fill the bucket to the brim, immerse the object, pull it back out, and then measure how much the water level went down because of the spillage. By this method, he could measure the volume of the crown and of an equal-weight chunk of gold. If the crown was pure gold, the two things should have the same volume. If the crown was made of a less dense metal, it should have more volume. He did the experiment, and found the metalsmith guilty.

Archimedes then thought about what makes things float or sink. This led him to Archimedes’ principle: when you’re swimming underwater, the pressure from the surrounding water pushes you up toward the surface. The force of this uplift is equal to the weight of the water you displace, that is, the amount of water that has the same volume as your body. This uplifting force is called buoyancy.

So will you sink or float? Gravity pulls you down with a force equal to your weight. Buoyancy pushes you up with a force equal to the weight of the displaced water. So, if you were made entirely of water, the two forces would cancel, and you would neither sink down nor float up. If you are heavier than the same volume of water, gravity wins and you sink. If you are lighter, gravity loses and the water pressure buoys you up.

It sounds like gravity and buoyancy are competing forces, but in fact, gravity causes buoyancy. Let's see how.

Diving Deeper

Why are snorkels so short? As a diver goes deeper, the water pressure increases, causing a greater and greater force on the rib cage. The air pressure in the snorkel does not increase significantly, it remains close to the surface air pressure.. The diver's breathing muscles have to fight the difference. Even a few feet below the surface, breathing through a long snorkel is like trying to suck air through a tiny straw.

Scuba gear solves this problem. The scuba tank has air compressed to 3000 pounds per square inch, about 200 times atmospheric pressure, or 200 atm. A regulator delivers air at a pressure that increases to match the water pressure as a diver descends. For every 33 feet of descent, the water pressure increases by 1 atm. So at 33 feet below the surface, the regulator delivers air at a pressure of 2 atm. This way, her breathing muscles get the needed assist.

Proving Archimedes' Principle

Why does the underwater pressure cause a buoyancy force equal to the weight of the water displaced by the submerged object? Look first at the case where the submerged object is water itself. Then we use the prevailing balance of forces to prove the principle.

Imagine a hockey puck at some depth. Both the bottom and top surfaces of the puck are being pushed on by water pressure, but the bottom is deeper, so it experiences a higher pressure. The difference pushes the puck upward. Buoyancy force is then due to the water pressure differences between the deeper and shallower parts of its surface. The buoyancy force does not depend on what the puck is made of; it's produced by the pressure gradient in the surrounding water.

Here's the clever trick. Suppose the puck was made of water Water surrounded by water neither sinks nor floats. Therefore, the downward force of gravity on the water puck and the upward force of buoyancy must exactly cancel each other. Now suppose that the puck was made of something else. Since the buoyancy force does not depend on what the puck is made of, it still equals the weight of the water puck. That's Archimedes' principle. Water settles into a stable force balance, where the pressure increases with depth in just the right way so that the water itself neither falls nor is buoyed upward.

Gravity causes buoyancy

Why is the pressure increasing as we go deeper? The answer is gravity. Think about a stack of books sitting on a table. As you go down the stack, the pressure between neighboring books increases. The top surface of the top book "feels" only the air pressure. The bottom book feels in addition the weight of all the books on top of it.

In the same way, the layers of water act like a stack of books. Water is not solid like a book, but does have weight and this creates increasing pressure as you go deeper. This gradient of pressure then causes the buoyancy force.

Climbing Higher

Archimedes' principle also works for air. At the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro the air pressure is about half of sea level pressure. What keeps the sea level air from rushing up the side of the mountain to equalize the pressure? Again, it's the force balance. The downward pull of gravity cancels the upward push due to the pressure gradient.

As a mountain climber ascends, the air becomes less and less dense, so each layer of air weighs less. But the pressure (and its gradient) decrease in the same proportion, maintaining the force balance. The force balance equation predicts that the density of the air drops by roughly a factor of two for every 19,000 feet of ascent. Kilimanjaro's summit is at 19,341 feet

Detailed Balance

We used the balance of upward and downward forces to predict atmospheric and underwater pressure. This kind of analysis is called detailed balance. We can figure out a lot of stuff about a system by realizing that in equilibrium, each process must balance the opposite process. A "process" could involve a flow of particles or a beam of light or a chemical reaction. So detailed balance helps us understand lasers and transistors and chemical reaction rates and many other things.

For science teachers and students

Here's a great science fair experiment. Measure the lifting forces generated by a helium balloon inflated to various sizes. You can use a postal scale to weigh a small weight with the balloon attached.

The bigger you inflate the balloon, the lighter the scale will read. The difference in scale reading between the inflated and empty balloon is the net lifting force. This in turn is the force of buoyancy (the weight of the air displaced by the balloon) minus the weight of the helium gas. One pupil did this experiment and graphed the lifting force versus the volume of the balloon, estimated using a tape measure. Her points fell on a beautifully straight line with a slope of 1 ounce per cubic foot. This agrees with theory: the difference in weight between 1 cubic foot of air and 1 cubic foot of helium is close to 1 ounce.

Comments