Special relativity: A wild visit to the train station

- brianaull

- Mar 20, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2025

Rumors of a speedy train

The year is 2105. Amtrak has recently started operating their ultrafast magnetically levitated trains. One of them goes through our small town. But they never stop here, because our platform is only 100 meters long and the trains are twice that long. The trains have synchronized clock displays on the sides of the cars. These are fast clocks: they measure time in "ticks." A tick is less than one five-millionth of a second. This is old technology, though. Our smartphones can snap pictures with equally precise time labels.

My friend Sofia wants to see if these trains are as fast as rumor reports. "I hear that they go 87% of the speed of light," she says to me. "That means moving the length of the platform in two ticks flat! Let's go down and snap some photos of the noontime train going through."

Our plan

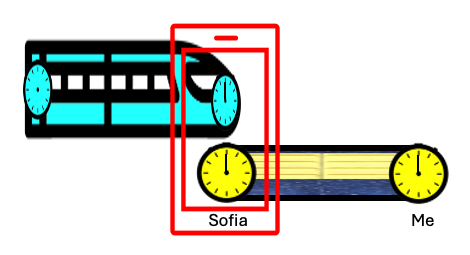

So we make our plan. "Sofia, you stand at the near end of the platform and snap the locomotive as it comes in. I'll be at the far end and snap the locomotive when it gets to me. Then you snap the caboose when it comes in." We sketch the expected sequence of events: Sofia's close encounter with the locomotive, mine with the locomotive, and finally Sofia's with the caboose.

Our surprises

With our smart phone clocks synchronized with each other and with Amtrak's Station Timer system, we take our positions on the platform. We set our Station Timer apps to allow the train's cameras to photograph us and track the clock times on our phones.

The train approaches. Snap. Snap, snap! At lunch afterward, we sketch what our smart phones recorded. It turns out very different from what we had planned.

"Are you sure their trains are all 200 meters long?" Sofia asks,

"Yep. All manufactured to the same specifications," I answer.

"Then how did the whole train fit in the station? Look, we snapped our ends of the train simultaneously. The train is compressed to half length. Also, are you sure that Amtrak synchronizes all the clocks on the train?"

"That's all automated."

"Well, our pics don't show them in sync. The locomotive clock is running behind ours, and the caboose clock is ahead of ours."

"I agree, it's weird. I also captured the caboose clock as it exited the station. Both the train's clocks were running at half speed. Tonight let's get on a Holo Call with my friend Zack. He works at Amtrak headquarters and can pull up the data logs from that train."

Zack's surprises

Zack stares at his monitor and asks me, "How does your town make do with that tiny 50-meter-long platform?"

"No, Zack, our platform is 100 meters long."

"Well, that's not what our pictures from the train measure!"

Zack shares his screen, showing our platform being only a quarter of the length of the 200-meter train.

Zach comments, "Hmm, your platform is compressed and you two look rather thin too. And you didn't synchronize your clocks."

I exclaim, "But we did! We were very careful about that!"

"Well, my pictures show your clocks out of sync with each other, and running at half speed."

The rescue

Zack calls over his colleague Carla, who was a physics professor before joining Amtrak. He shows her the paradoxical data. "They measure our train as shortened and with slow clocks. We measure their platform as the thing having those symptoms. I'm stumped." Carla laughs and says, "Stumped? That's what you get for having worked as a lumberjack. They didn't warn you about these bizarre effects?"

Zack explains, "I missed my new employee orientation because I was out sick that day."

She continues, "So 200 years ago, this guy named Albert Einstein was working as a patent clerk in Switzerland, but his real passion was physics. In his spare time that year, he published his theory of special relativity, along with three other groundbreaking papers. His idea was simple. He was familiar with Maxwell's equations, which describe the motion of light. The speed of light appears in these equations as a universal constant. Einstein took this universality seriously."

I laugh and ask, "You mean before that we were taking it frivolously?"

Sofia chimes in, "Yes, I remember a teacher explaining this! If you are standing and watching a sunset, the light hits your face at the speed of light. You can't make it hit your face faster by running toward the sun, no matter how fast you run. It still hits your face at this same universal speed. I thought that was odd. You can certainly make sleet hit your face harder by running into it."

"And the consequences are odder," Carla explains. Looking at me, she continues, "You and Sofia used the platform as a ruler to measure the length of the passing train, and your clocks to time events, such as Sofia's close encounter with the caboose. The train's system used the train as a ruler to measure the length of the passing platform and its clocks to time the same close encounter. Einstein's equations translate the "where" and "when" of such an encounter from the values measured on the platform to the values measured on the train. The equations predict that we measure things we see swiftly moving by as compressed and their clocks as slowed down."

I exclaim, "What shocks me the most is that we don't agree with the train's system on what events are simultaneous! Sofia's close encounter with the caboose and my close encounter with the locomotive happened at the same time on our clocks. But the train's clocks and cameras measured my close encounter as happening sooner!"

Carla concludes, "Yes, anyone not shocked by special relativity hasn't studied it."

Comments